gan

THE PEOPLE’S CLIMATE MARCH. OR, “HOW TO TELL A STORY WITH 400,000 PEOPLE”

A NARRATIVE APPROACH TO MASS MOBILIZATION

How do you transform a mass mobilization of thousands of voices and hundreds of messages from a cacaphony into a chorus?

As the date of the 2014 People’s Climate March approached, we knew it would be big. We had been organizing for months, and it felt like everyone was coming. On the day of the march, we could have all shown up and in a typical fashion vied for attention in a fight over who gets to be 'first', while the multiplicity of messages would have at best been a mess, and at worst, appeared to others to be in conflict with each other, or most likely just cancel each other out. All the individual work of tens of thousands of people that went into slogans, signs, banners would simply get lost in the jumble. Like so many mass marches before it, the largest climate march in world history would have been a wash, un-intelligable to the media or the larger public.

Or we could do something different.

As one of the lead organizers of People's Climate Arts, the arts working group tasked with facilitating art production for the march, I approached the central coordinating body of the march, the MST, with a proposal to totally re-concieve the structure of the event. We would use the power of story, and it's structure, to make sure that all voices were heard, clearly and coherently, and for maximum impact.

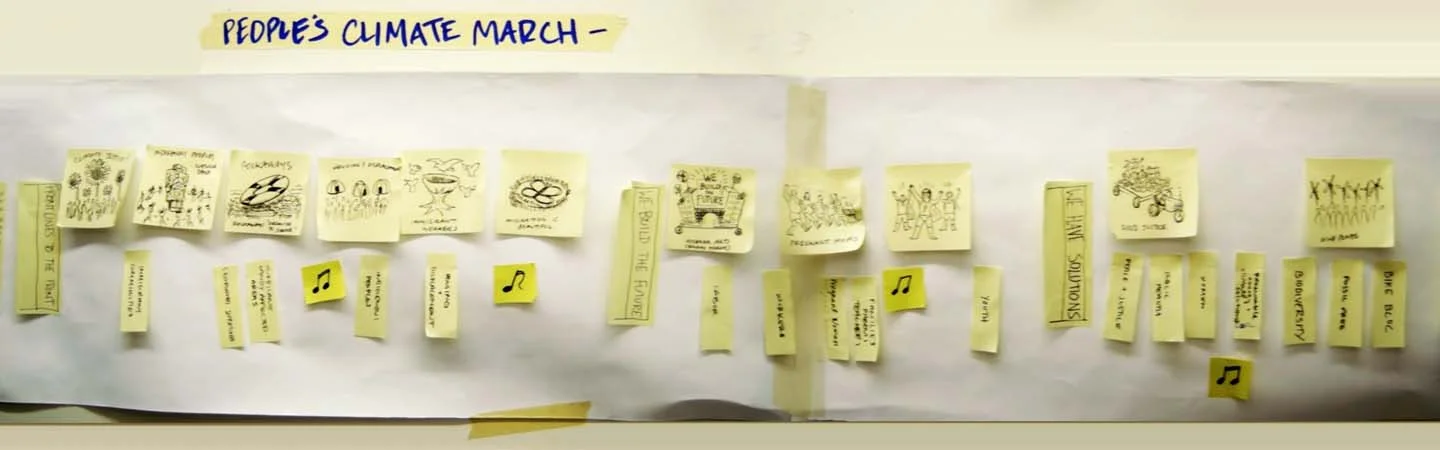

In conversation with numerous groups over many weeks, we crafted a single, unified story with multiple chapters, each with it's own themes, messages and leading groups. Intense debates were had over framing, priority, and wording, but ultimately, it was a story that had it all - our heroes, our struggles, the villains, a concrete vision for change, and a space for everyone. On the day of the event, it the story came to life across 50 New York city blocks and was told by over 400,000 storytellers.

Each chapter was lead by huge banners and parachutes that defined section of the march, each with it's own symbols. Within each section there were monumental works of art that clearly communicated that piece of the story.

Hundreds of organizations – from racial justice activists to beekeepers – were able to find their own powerful place in the larger story, rather than get lost in the crowd. Hundreds of thousands more individuals showed up on their own to telling their chosen part of the story through their own handmade artwork and signs. The media, rather than try to give their own spin on what was happening, simply took entire sections of the narrative and repeated it, often verbatim.

What was the result? The People’s Climate March shifted the larger narrative around climate in our country. It reframing what the movement was about, shifting from the legacy of Environmentalism (a largely White lead movement focusing on conserving nature and animals irrespective of people) to the Climate Justice movement (a movement focusing on a far more inclusive understanding of defending both nature and communities at risk, with leadership coming from frontlines communities). As part of this, we were able to communicate the vast complexity of the Climate Justice movement, and it’s many important threads and movements within.

Epilogue:

Like any good story, the PCM Narrative continues to be retold. Key messages continue to circulate in the media. Subsequent historic mobilizations have used both the same strategy, and even particular PCM messages, in their own actions (like in Chicago, and France). More importantly, it has caused organizers to break out of conventional mobilization structures and use more creative, compelling frameworks to organize themselves, and to speak to the larger world.

WHY USE NARRATIVE?

It's not about numbers: The typical goal of a mass mobilization is to get the highest number of people on the streets, and then use that number to move decisionmakers. The problem is, the story about a number is not a very compelling story. It's just a number. Also, making a number your goal is almost always setting yourself up for failure. If you don't achieve it, you failed. If it's not bigger than the last one, you failed. If the number gets debated - and it almost always does - you failed. However, telling a rich, engrassing story that says who the heroes are, who the villains are, what the stakes are - that moves people in an entirely different way.

It's about Meaning: Meaning is what gives an experience impact. When we turn a list of talking points into a compelling, memorable story, we can create meaning. Asking people to show up with a sign and just march from point A to B offers people very little meaning. However, asking people to be responsible for being a part of an epic story, makes it a much richer, and lasting experience for those involved, as well as for those witnessing it..

Clarity: If you are successful in getting thousands of people together, all with their own signs and perspectives, you may have created a messaging moshpit. The media and larger public are un able to clearly understand your message, particularly if it has many layers. A narrative helps oganizes all those voices, ideas and issues into one accessible, unfolding message.

Coherence: Narratives have an accessible, but complex structure, with multiple characters, high points and low points, darkness and light. Todays movements are also complex. A narrative allows you to organize all the many groups and their messages into a single structure, without oversimplifiying or diluting it. That way, you don't require everyone to reach consensus, but they can still be coordinated and united. Trying to reach consensus often reducing a message to it's lowest common demnominator. In other words, weak sauce. In contrast, narrative allows you to keep it full of flavor, and spicy.

Diversity: Narratives have different moments, or chapters, where you can start fresh. This allows for many 'fronts' of the march, so everyone is not fighting over being first. It creates space for multiple messages to be heard, and groups to be seen.

Equality: A story can amplifies the importance of messages or groups that have been heard less, helping to ensure that the most powerful groups with the most resources do not dominate the message.

Participation: Story created an open structured that allowed unaffiliated individuals (i.e. the majority of participants) to work autonomously from your central command, but still within a structure you helped craft. They can choose d a meaningful part of the story they want to embody or represent, and then show up on the day of. It decentralizes the labor and cost but maintains unity.

Reframing: A new story tells us that things have changed. The way you tell a story can foreground certain groups or issues, that allow you to tell the story in a transformative way that has not been heard yet.

Logistics:

Control: If you don't tell a clear story, the media will tell it for you. And get it wrong. With the narrative the media will often reprint entire sections of your story as is.

BUT...

Art is a means to communicate the meaning of our actions, but it is not a substitute for action itself. Focusing more on the narrative than creating it together with communities, or in the goals of your strategy before, during and after the action, runs the risk of creating an art piece with no impact. The most powerful story is people taking courageous action and that should always be the center. Build your art around that.

APPENDIX:

The Peoples Climate March Narrative

"Frontlines of Crisis, Forefront of Change"